On sleep aids: If you’re lucky, falling asleep is like blinking or gulping saliva—an automatic function. You go to bed, and your brain and body simply do their thing, cycling through stages of NREM and REM. In the hours before you wake from prolonged rest, adrenal glands begin pumping cortisol through your body. And then you are vertical and alert… ready to tire yourself out, then slip back into slumber with little-to-no conscious thought.

Since I was small, I've been a hapless sleeper. I wake throughout the night. Have nightmares. Get restless. There’s no jump-cut between conscious and unconscious states, just a slow, agonizing transition. Thoughts multiply like rabbits in springtime. Reading books before bed only makes them more unruly. I end up sitting upright, underlining passages.

Gaspare Traversi, Teasing a Sleeping Girl (ca. 1760), via The Met

Excluding pills, the best way I’ve found to fall asleep is an audiobook. Drown your voice in someone else’s. I used to listen to cassettes my parents would buy, recounting adventures of a fictional British schoolboy named William. According to the Wiki page, these drew criticism for unsavory plot points. I wouldn’t have known; I always fell asleep in five minutes.

Most nights for the last two years, to coax myself into slumber, I’ve played the same episode of Gunsmoke radio. The episode is called Kitty and was released in 1952. It starts off quiet; no startling sound effects. The plot involves a new guy in Dodge City, Kansas, who becomes infatuated with Kitty Russell, saloon proprietress. His obsession eventually gets violent—and Kitty shoots him, so I've read—but I’m asleep by then.

The trick with audiobooks, or old radio shows, or podcasts, is to keep the volume very low. You focus on making out the disembodied voice of the narrator, without things being loud enough to actually follow along.

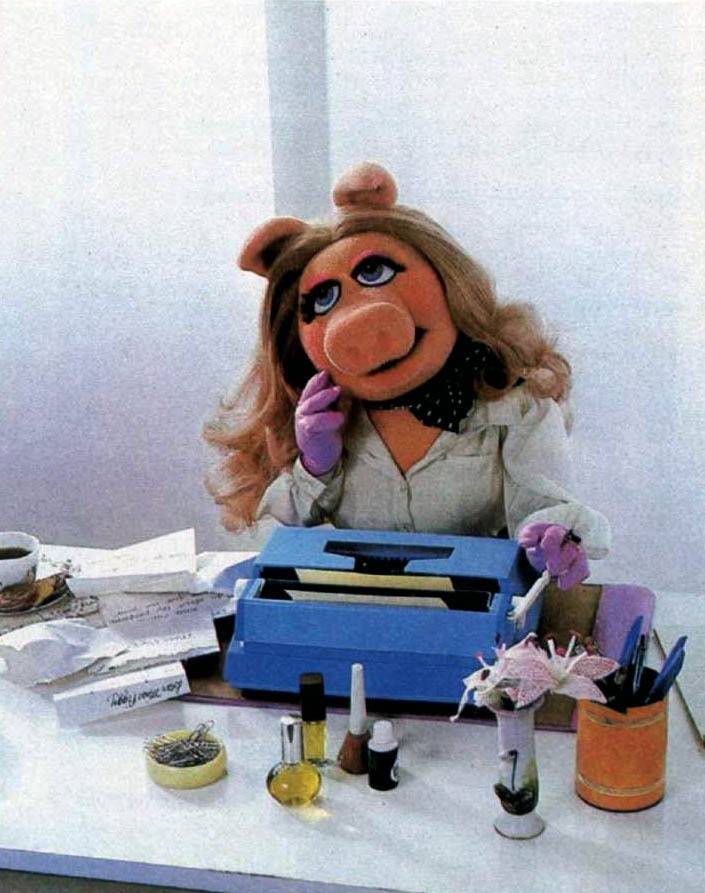

I am in the market for a new anodyne. On r/hypnosis, I see someone trying to locate a self-hypnosis cassette that they owned in the 80s. “The presenter had several different recordings,” the Redditor writes, “and I think he sold them from the backs of magazines. He often talked about sinking down into a relaxing purple liquid. Maybe it was pink.”

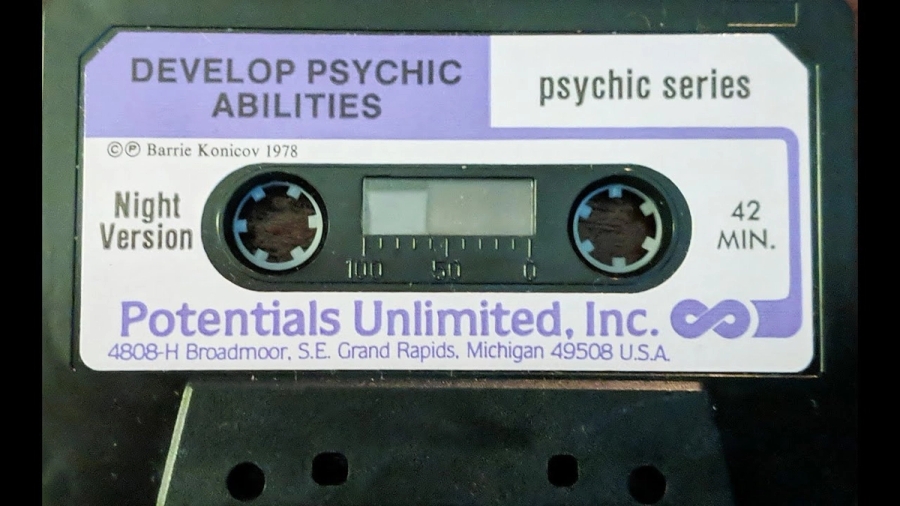

I learn the sleep tape is by Barrie Konicov, who was once jailed for tax fraud and who ran as a Libertarian for the Michigan District 3 seat in Congress. He received less than 2% of the vote, but at his peak sold around a million self-hypnosis tapes a year. Konicov’s tapes were released under his own company, Potentials Limited, and were sold at Barnes and Noble. They begin with “Hello, greetings, and welcome. Welcome to a new beginning. That's right, a new beginning..."

He talks not of purple or pink, but orange elixirs, less common in the pulsing light techniques of early hypnotherapists. I like the idea of drowning in a sunset.

Konicov, who died in 2018, had no hypnotherapy credentials beyond a few weekend seminars. He did have a degree in marketing, selling hair curlers and life insurance before turning to self-help.

I read that his messaging is a little like Scientology, in that it suggests negative experiences from our past lives are the basis for present hang-ups. I order a tape anyway. I’ll be asleep by then.

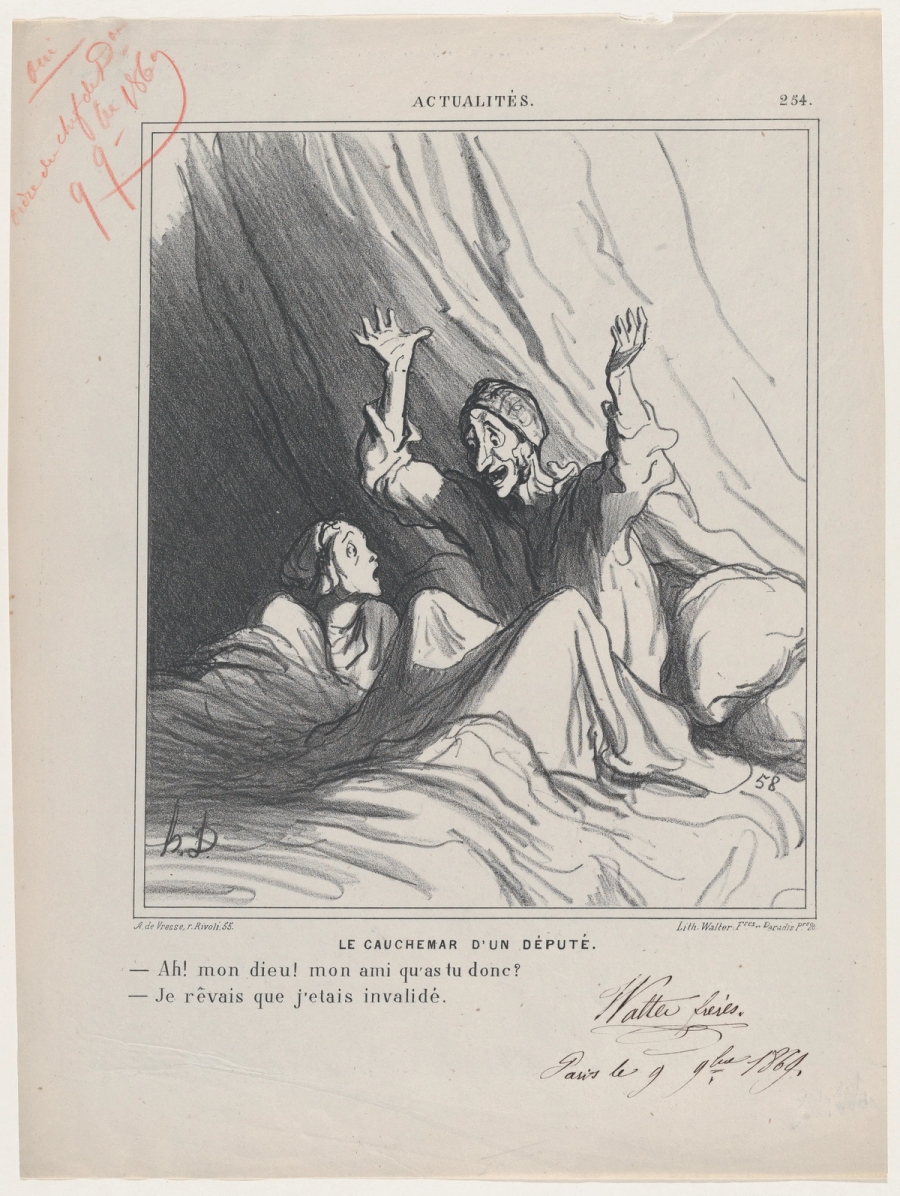

A deputy's nightmare: –Oh my friend, what has happened? –I dreamed I was invalidated, from 'News of the day,' published in Le Charivari, December 7, 1869, via The Met

Seven movies I watched this year (in no particular order):

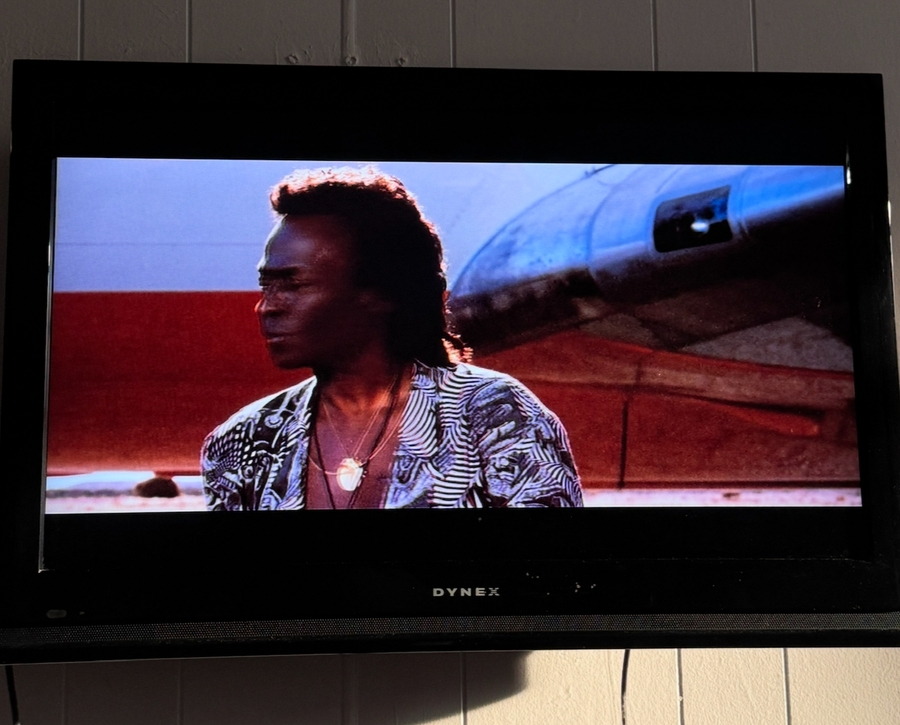

1. Dingo (1991) - A friend recommended this over dinner. It stars a dingo trapper and trumpeter who lives in outback Western Australia. He's idolized musician Billy Cross (Miles Davis), ever since Cross' plane made an emergency landing nearby and he played an impromptu gig. It's the only movie Davis speaks in, and was released just after his death.

2. The Fly (1986)- Forgot that I'd already seen this. Remembered when Jeff Goldblum morphed into the giant fly.

3. Dead Calm (1989) - Based on a 1963 novel by Charles Williams, this claustrophobic thriller is set on a boat with a cast of three. Nicole Kidman is just 20 years old and playing a mother; Billie Zane is a menacing pretty-boy predator. The ocean plays itself, soporific and violent, indifferent to life or death. FYI I loved this movie. I watched it alone on a clammy summer night.

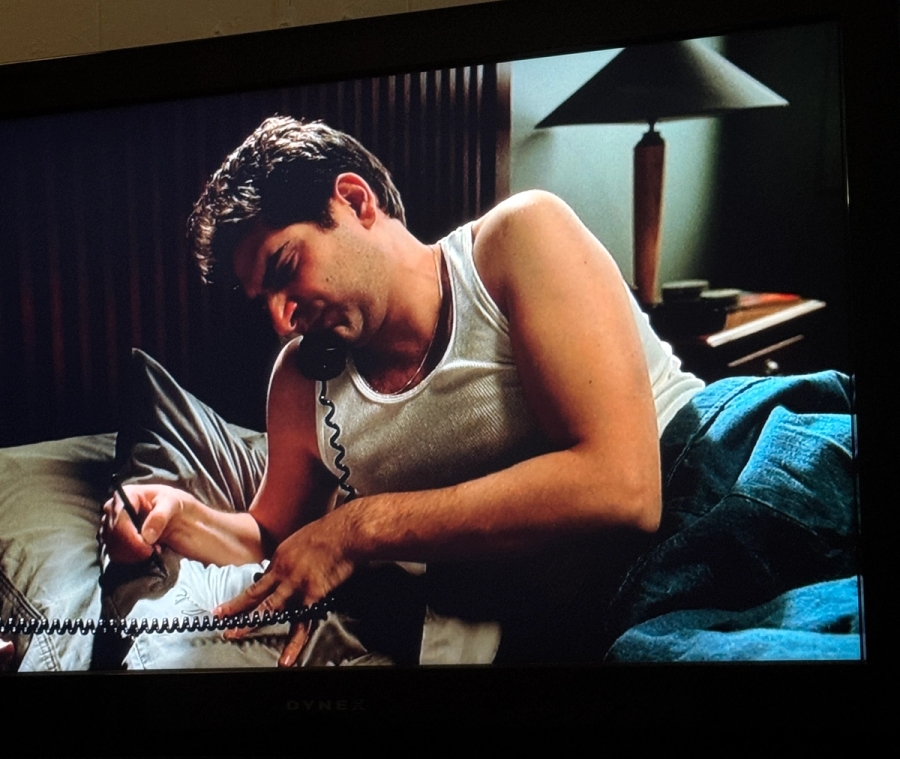

4. Baby Boy (2001) - A coming-of-age movie starring Tyrese Gibson as Jody, a young-ish slacker dad who lives with his mom in LA. The happy ending is happier for the men; women are eventually rewarded with better versions of their partners and family members, only after being dragged through it. Teddy likes the scenes where Ving Rhames beats up Tyrese Gibson. I like when Ving sharpens his dice with a kitchen knife.

5. Delirious (1991) - 27% on Rotten Tomatoes. 110% rating from me. It's a comedy about a soap opera writer, played by John Candy, who finds himself trapped inside the TV show he's been writing.

6. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1972) - Made me homesick. Doesn't feel like home at all.

7. Serial Mom (1994) - Kathleen Turner plays a grimacing June Cleaver-housewife and serial killer in this John Waters-directed suburban slasher satire. There's a cameo from Patty Hearst and Ricki Lake play's Turner's daughter.

Teddy and I got married at the courthouse last week (!), then had a party at Bar Oliver. My friend Trey, who runs the fragrance brand Serviette, made us a fragrance as a party favor. We watch westerns nonstop—Teddy and I, that is—so there were notes of hay and sawdust and lasso rope. He made 100 small bottles of Gunsmoke, all gone now, with labels designed by my brother. Someone uploaded it to this fragrance website after. It's listed as discontinued, which I found sort of funny.

Recently, I profiled Martyn Stewart for the Australian edition of Esquire—you can read it online here. (It was also syndicated in Esquire Singapore). Stewart is an audio naturalist who's recorded over 97,000 sounds from the natural world, including the northern white rhino, the Panamanian golden frog, hurricanes, earthquakes, ant colonies, and the insides of trees.

I met Martyn around 2023 through Tin&Ed. They were collaborating with him on their artwork Deep Field, an interactive AR and sonic experience designed for children. I wrote the artist text for the show, which has toured AGNSW, the Getty Center, and MoMA. In it, children use iPads to illustrate fantastical plant parts and add them to a database, filled with flora drawn by children across the world. The commingled artworks bloom as 3D plant structures all around them.

The kids go exploring the world they've made, and Martyn's soundscape plays as they roam: rumblings, warblings, squawks. Later, I got in touch with him for this story. We did some interviews over Zoom, then at his home in Melbourne Beach, Florida.

Here's some disposables I found from that trip.

Martyn Stewart in his studio

Things I like, on February 16: the snow-blanketed beach in Atlantic City, viewed from the 39th floor of Bally’s hotel-casino where I was recently holed-up; happy hour seafood at Docks Oyster House in AC (get the Maine clam chowder and the tuna tacos); Carl Van Vechten’s studio portraits of Alvin Ailey, taken in 1955, some of which I caught on the last day of Ailey’s Whitney retrospective; slipping a rock into my pocket;

the word punnet to refer to a supermarket-issued container used for berries (I only learned last week that plastic container is as precise as American English gets); the haunted image of a golden egg floating through space in George Sluizer’s 1998 film The Vanishing, adapted from Tim Krabbé's 1984 novella The Golden Egg (I enjoyed this reviewer’s framing of the film as “a march backward through time”);

numerous shades of roses, including yellow roses, my favorite to give and receive (almost cosmic timing: Dolly Parton’s Yellow Roses dropped a week before I was born), a red "eternal rose" from Teddy, who gets it; artificially dyed blue roses, especially ones with jolts of neon along the petal edges; a scene from The Sopranos where Christopher takes notes on his pillowcase using marker;

and Serviette, a handmade line of fragrances by my friend Trey Taylor, which another friend, Osman Yerebakan, wrote about in T List this week. (I make a cameo in Serviette's campaign, shot by Tina Tyrell.) You can find me in T List too this week, on Wet Reckless, Issy Wood’s new show at Michael Werner Gallery in Beverly Hills. It's made up of oil paintings based on photographs. Pictures of pictures, she says. Her subject matter is American Seduction, made grubby: guns, fast cars, fur coats.

Snow beach, Atlantic City

Alvin Ailey by Carl Van Vechten (1955), silver gelatin prints

Everything is a notepad, per The Sopranos

A Serviette bottle, photographed by Tina Tyrell

Issy Wood, “Woman with guns”, 2024, oil on linen, via Michael Werner

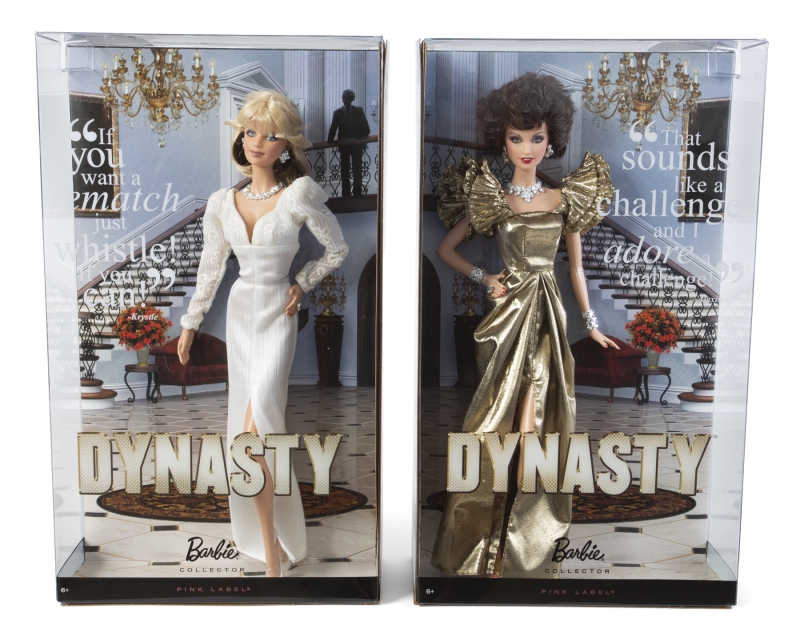

Doll chronicles:

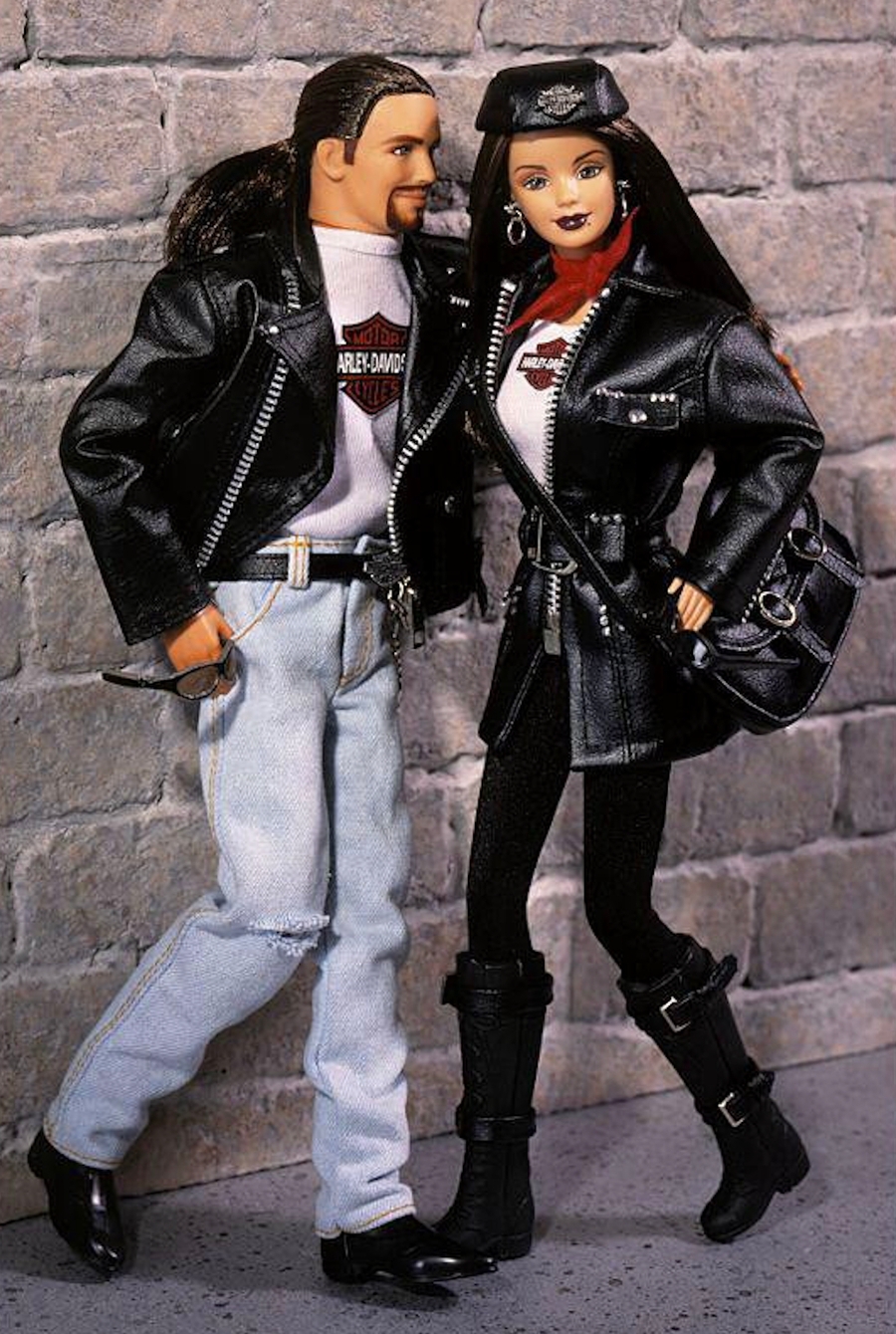

Perusing eBay, then Barbiepedia recently—I’m the daughter of a doll collector and cross-generational behaviors die hard—I happened upon two figurines tempting me to expand my paltry Barbie collection. (The collection is one of one; she’s from the 2011 Harley-Davidson line. I bought her at The Big E, a multi-state fair in Massachusetts, which hosts an annual butter sculpture and sells a glut of hot tubs.)

First Barbie: an admittedly unconvincing Alexis Carrington Colby of Dynasty, clad in ruffled gold lame (based on an iconic Nolan Miller gown) and tiny faux diamonds. The effigy was produced in 2010 for Newly Nostalgic, an 80s throwback collection. According to Barbiepedia, the plastic 11.5 inch-tall doll “cannot stand alone,” which is character assassination. I want her, in spite of it. (A strangely charming backup are these World Doll Dynasty collectibles. The Krystal has seen a lot.)

I’ve been watching Dynasty a lot again, and keep thinking about Alexis’ angular, high collared skirt suits by costumer Nolan Miller, who was given a $30,000 budget per episode by producer Aaron Spelling. Miller also did the grey-lavender dress and cape-with-stole Dominique Deveraux wears in her very first scene, which moves so fluidly.

Also of interest to me: eight Hard Rock Cafe-themed Barbies, sold with logo-marked pins..... a reminder that anything is a collector's pin if you write it on the box.

Dolls on film:

If you’re inclined toward dolls, may I recommend Magic (1978), a proto-Chucky movie about a Vegas magician's unraveling? It stars Ann Margaret, Anthony Hopkins, and Fats, Hopkins’ murderous ventriloquist dummy. It’s heavy handed and sometimes wooden (especially when it comes to Margaret's dialogue), but that didn’t bother me. Watched it with my boyfriend and his dummy, Skip.

Three things (new exhibitions for T Magazine)

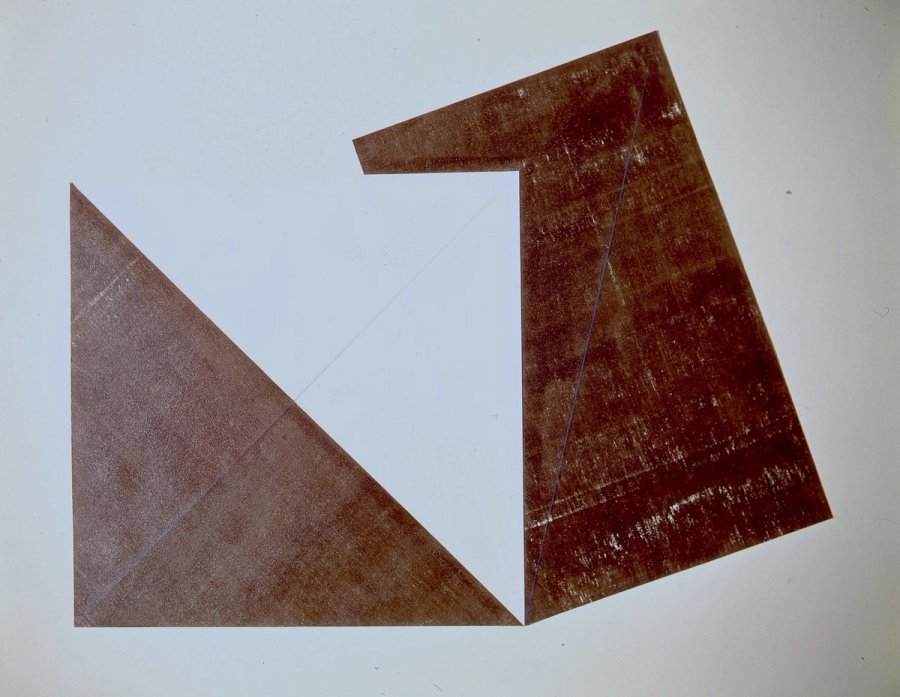

1 . Read me on Dorothea Rockburne, 95, whose first major EU retrospective just opened in London. A lot of the work is very fragile and hasn't been seen before outside the US. “I still take pictures of plants in Central Park,” she told me, perched on a blue sofa in her Soho loft and studio, “and even downstairs, in the building courtyard. There’s benches and bushes there. I like watching how nature behaves.”

2. Read me on Nour Mubarak’s mycelium opera Dafne Fono—an anti-colonial, multilingual, surrealist restaging of Ovid’s Dafne—now on show at MoMA.

3. And on Lucas Arruda’s new paintings show at a Zen Buddhist temple in northern Kyoto.

Dorothea Rockburne, Golden Section Painting: Rectangle/Square, 1974, Linen, gesso, glue, varnish, colored pencil, via Bernheim Gallery.

Post Venice Biennale, Jeffrey Gibson installed a football field-sized show at MASS MoCA, much of it centered on expressions of Two Spirit states of being. I loved a two-channel video made in partial homage to Leigh Bowery's 1988 performance at Anthony D’Offay Gallery in London (where he postured before a one-way mirror installed in the gallery's windows). For i-D, I reported on the installation's opening weekend, which included performances by Takiaya Reed and Anohni. Read it here.

This new website is thanks to my brother Matthew and his team at Studio Matthew Roland Bannister. It was built by Rosen Tomov.

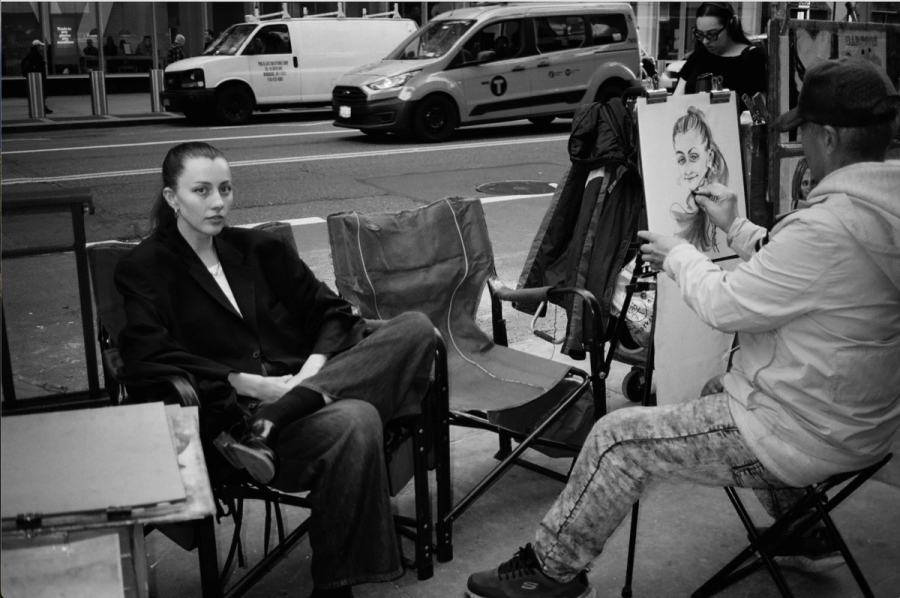

Thanks too, to Poppie, who took these portraits for me outside the library, and inside an OK place to get a martini in Times Square, Bubba Gump Shrimp. (Don’t get the shrimp.)

P.S. To read diary posts in full, click/swipe on text.

Things I like in early October: the blazing sunburst in this 1984 oil painting by Jutta Koether; night strolls with Frutta e Verdura on loop; a childhood photo mailed to me by my dad, in which my brother and I crouch near a fallen blue gum in the scraggly bushland bordering our home; spotting cast crossovers in soap operas, like Indian actor Kabir Bedi, who’s in Dynasty (original series, one episode) and Bold and the Beautiful (seven particularly insane episodes released in 1994-95);

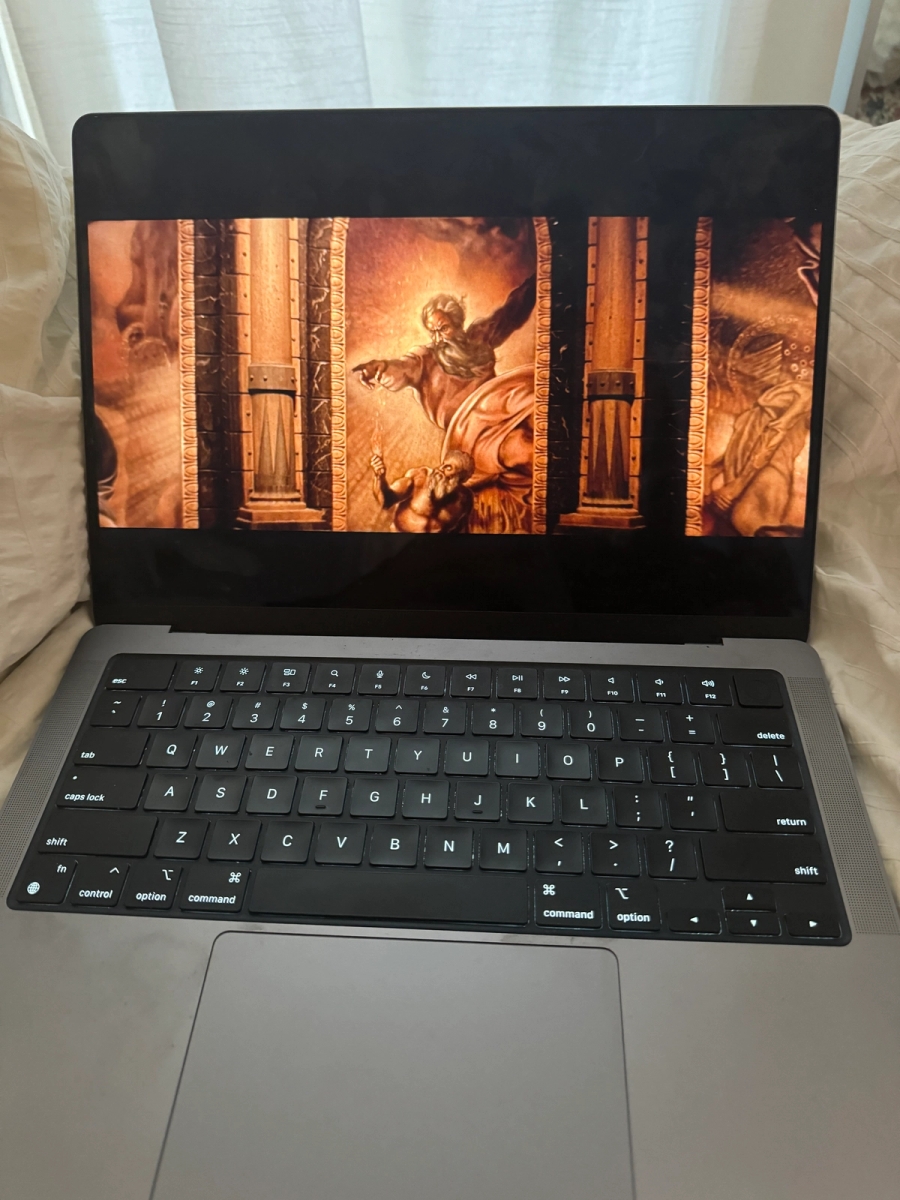

sautéed eggplant with Sugar Bob’s smoked maple syrup; keeping tabs on mother-of-pearl gambling chips up for auction (I have an incomplete set from Chelsea flea); using tweezers to smoke a roach (very elegant); the closing shot in Flatliners (1990 version), a gradual dolly-out of a mural in which the titan Prometheus steals fire from Mount Olympus (the whole movie, in which med students "play God" by stopping their hearts for minutes at a time, is shot like a Greek tragedy);

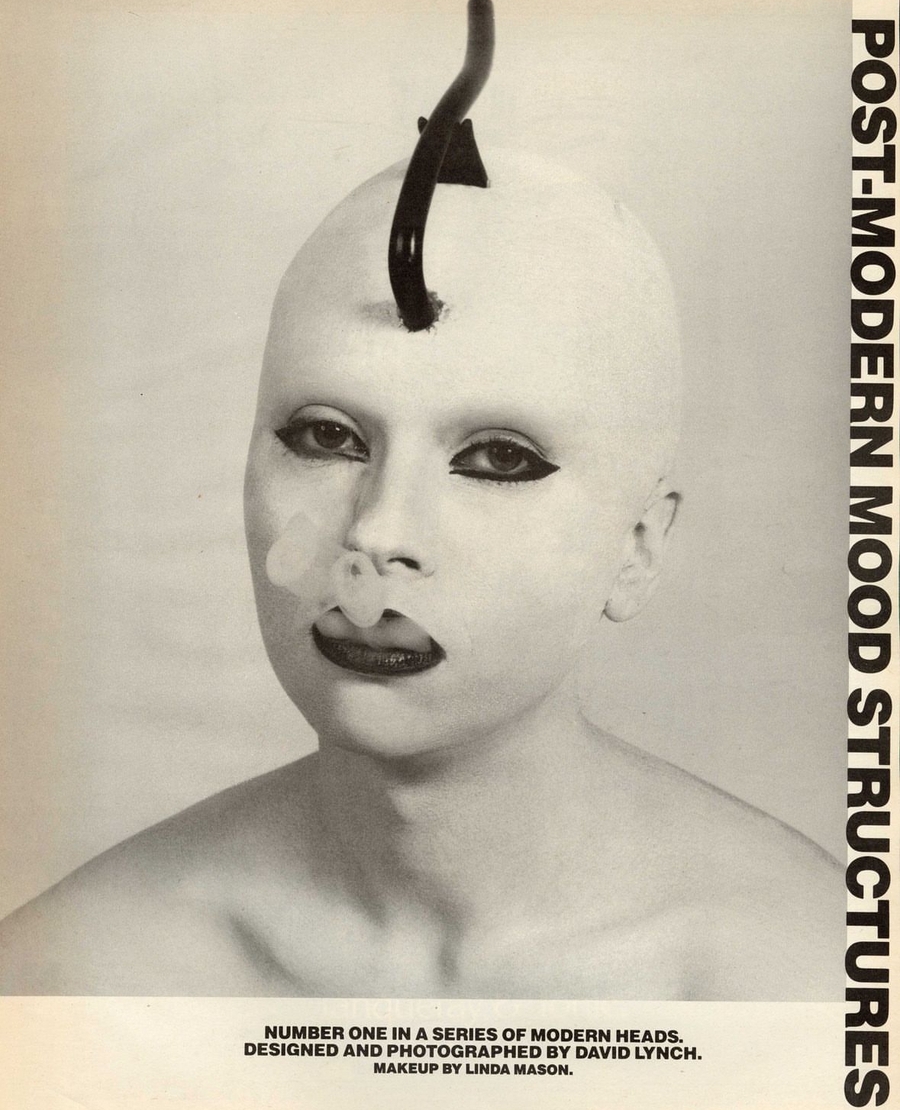

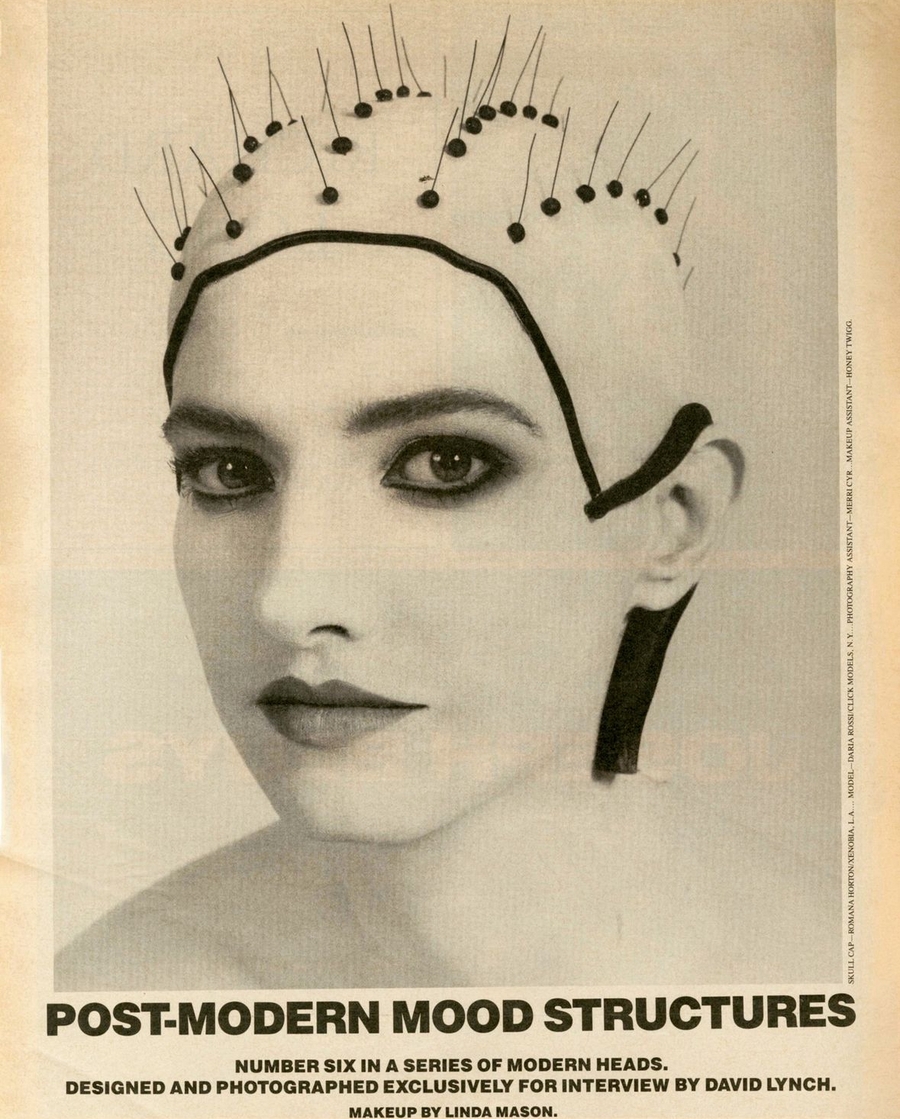

six photos of "modern heads" by David Lynch for Interview in 1988; a small, Brutalist sculpture of a sun, which I splurged on, having found it was made in the workshops of excommunicated Benedictine monks (apparently the chapter was getting into psychotherapy, which the church didn't approve of); Teddy FaceTiming me from a Motel 6 carpark, or a Yosemite campsite, or the blacked-out casino where he’s eating breakfast, or a green room, or a convenience store with two pool tables at the back;

this passage on silence in The Hearing Test, Eliza Barry Callahan’s novel about an artist who suddenly goes deaf:

“I began to note simple and unremarkable patterns around the word, such as that seeing, staring, hanging, or watching are often coupled with silence. That the adverb completely often precedes silent. That the verb fall often precedes silent. That the architecture of silence is the gaze. That silence is without transition. That silence is dressed as an injury.”

The end of Flatliners.

Post-Modern Mood Structures by David Lynch for Interview, 1988. Makeup by Linda Mason and Paul Gobel. Found via archivist Nikki Igol, who is the director of image research for Pat McGrath.

(I interviewed Igol, and her archivist partner, Nelson Harst, years ago for The Face, which you can read.)

Motel 6 parking lot in Sutherlin, Oregon, via Teddy.

Been writing a lot for T List. Read me on Meeson Pae’s first solo show at Anat Ebgi (here); Arlene Shechet taking Storm King (here); crumpled tissue paper-on-canvas by the late Nancy Brooks Brody (here); Rick Lowe's new monograph (here); a fantasy sitting room by Mexico's AGO Projects (here); and a Gagosian presentation of furniture designed by the Italian writer, editor, activist, and fascist-turned-communist, Curzio Malaparte.... aka Kurt Erich Suckert of Casa Malaparte (here).

A console conceived by Curzio Malaparte. Photo by Dariusz Jasak.